Bridges to Prosperity’s AI-powered mapping shows the promise of infrastructure for good while raising questions about tech colonialism

Delayed reaction, maybe? I was hunting around for AI for Good projects around the world recently–call it learning about our mission-driven clientele! Or call it finding fodder for a monthly newsletter to pair with all the other content creation I’m working on! Either way, productive and enjoyable to actually get to read about positive ways that my bread and butter (AI) exists in the world.

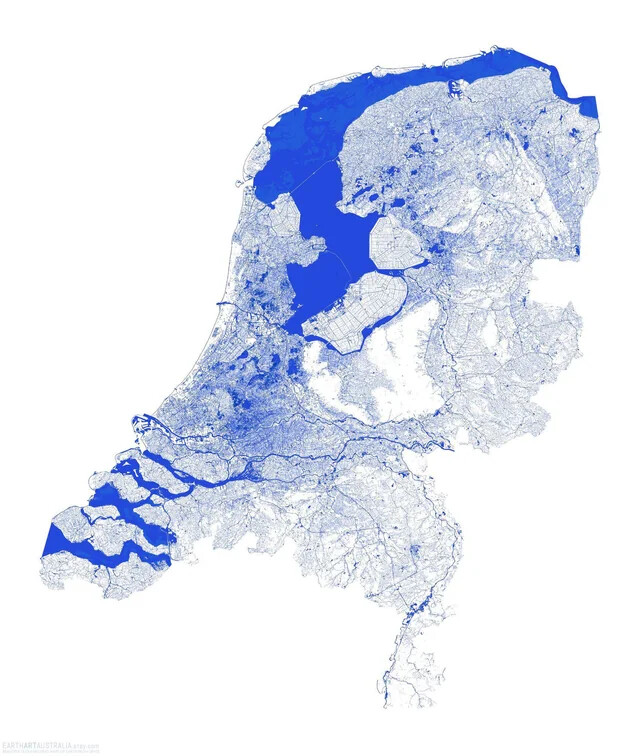

There’s one really neat news item I missed from May, though, about infrastructure 501(c)(3) Bridges to Prosperity surveying the land for waterways using AI. It turns out that over half of the waterways that exist in Africa are unmapped. In other words, if you look on Google Maps, there won’t be lil blue lines like the plethora of equally (in)significant ones you’d see on a map of our new home.

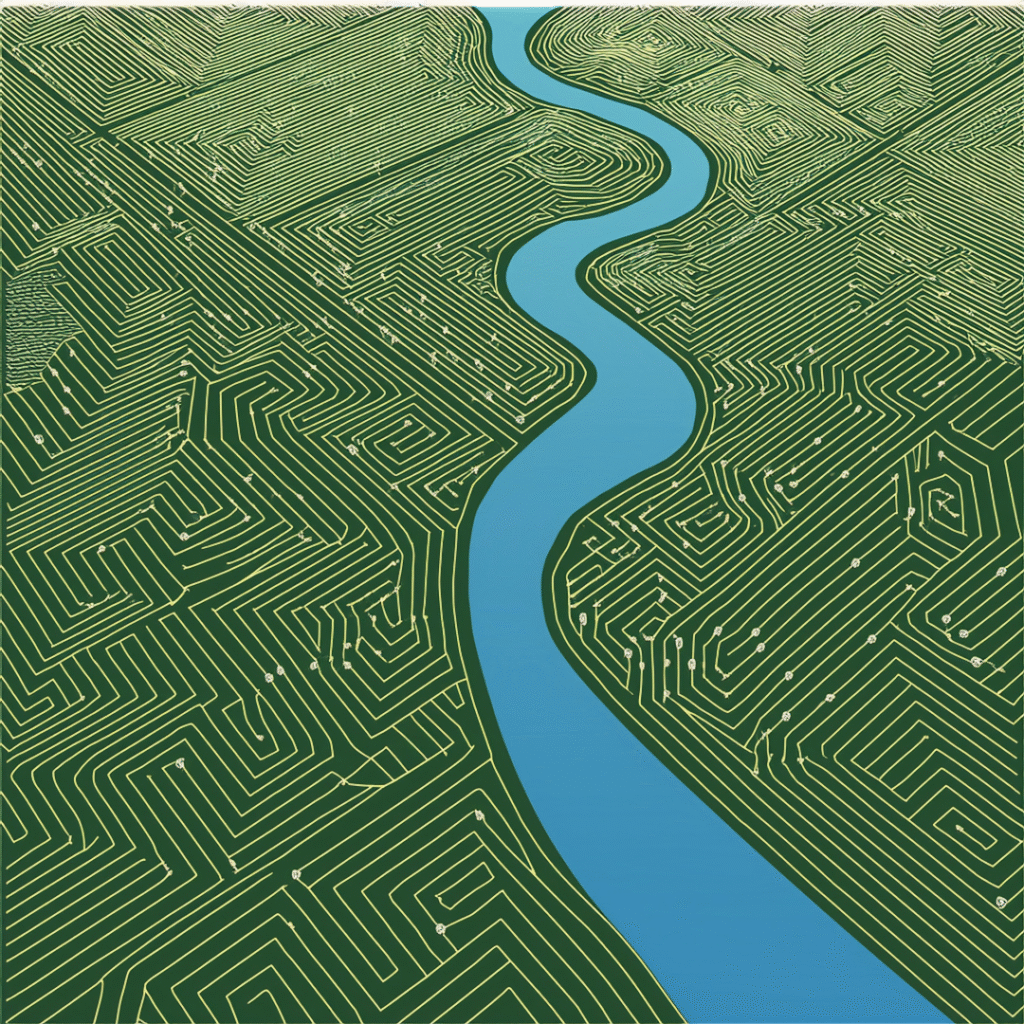

Waterways come and go. Folks native to these lands have a good intuition about their lands’ passability, but modernizing bridge infrastructure gives the chance to create passability. It also requires surveys that satellite data just hasn’t reliably drawn. Data from satellites just doesn’t have the resolution to detect the patterns that would indicate a waterway that is often dry, and the incentive to map these out for distant rural communities in the Global South has lagged.

But so far, bridges coordinated and built by the nonprofit help substantially increase economic activity in the isolated rural villages they serve in East Africa.

How is this nonprofit organization outperforming hundreds of years of colonialist topography and a half-century of satellite data? Well, sadly, it isn’t Atsushi Tero’s slime mold that can predict the best pathway volume for Japanese rail. This, to me, seems the most novel solution, but I suppose isn’t as scalable (or as relevant to isolated living hubs).

Instead, Bridges to Prosperity worked with Better Planet Laboratory to create an AI model, WaterNet. Pre-existing satellite information, radar, and, funnily enough, a fitness tracking app helped create layers of data to infer elevation and vegetation patterns, thus, where unmapped waterways (and roads) exist. From there, bridges have the impetus to be built.

I had recently read techbro/nature boy (natech broy?) James Bridle’s Ways of Being, and felt his palpable (and bro-y) excitement about the magic potential of mycelium, bugs, and yes, slime mold to help us solve some of the world’s burning problems in context of cybernetics. But recreating what (we’ll say) God meant these creatures to do on Earth to satisfy the modern needs of humans sort of rubs me wrong. Nevertheless, the fact that Africa’s territorial tapestry has now become the domain of tech colonialists probably doesn’t bode much better, despite Bridges to Prosperity’s best efforts.

Couldn’t we also be opening these isolated communities up to more degradation in the form of urbanization, mining, or fossil fuel surveys? (Or, uhhhh, data centers?) AI doesn’t simply passively hold this data–it’s just waiting to shout it from the rooftops, and more often to rapacious magnates than to people who are just scraping by.

Oh, how quickly the exciting promise of AI can turn on us.

My hope is that infrastructure nonprofits, perhaps the least likely to be devastated by USAID cuts, will focus on projects that stem the tide of desertification, actually harness the power of water for feeding folks, and perhaps attract the curiosity of Dutch water engineers, who for hundreds of years, have kept a country that should be underwater well-afloat.

Need to know the latest on AI Risks? Check out how we can help you build policies and detect red flags.

How do we align AI with mission-driven organizations? Check out our do’s and don’ts.

What problem can AI never solve? Find out the future of intelligence.

Leave a Reply